As the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples on 9 August approaches, I feel deeply connected to this year’s theme, ‘Protecting the Rights of Indigenous Peoples in Voluntary Isolation and Initial Contact.’

Starting in 2008, my six years in Africa as an Environment and Community Specialist for BHP Billiton Exploration were a lifetime opportunity. I experienced firsthand the continent’s diverse cultures, landscapes, and chequered and complex histories; my passion for travel and photography took me to 32 of the 54 countries for work and holidays.

Living in Angola, Zambia, Gabon, Ethiopia, and eventually Tanzania, a key part of my role involved community engagement. As a member of reconnaissance teams, I frequently engaged with traditional leaders, chiefs, royal establishments, municipal authorities, and community stakeholders in remote areas. We aimed to seek their support and consent for our exploration activities and environmental and regulatory approvals and learn from their invaluable local knowledge.

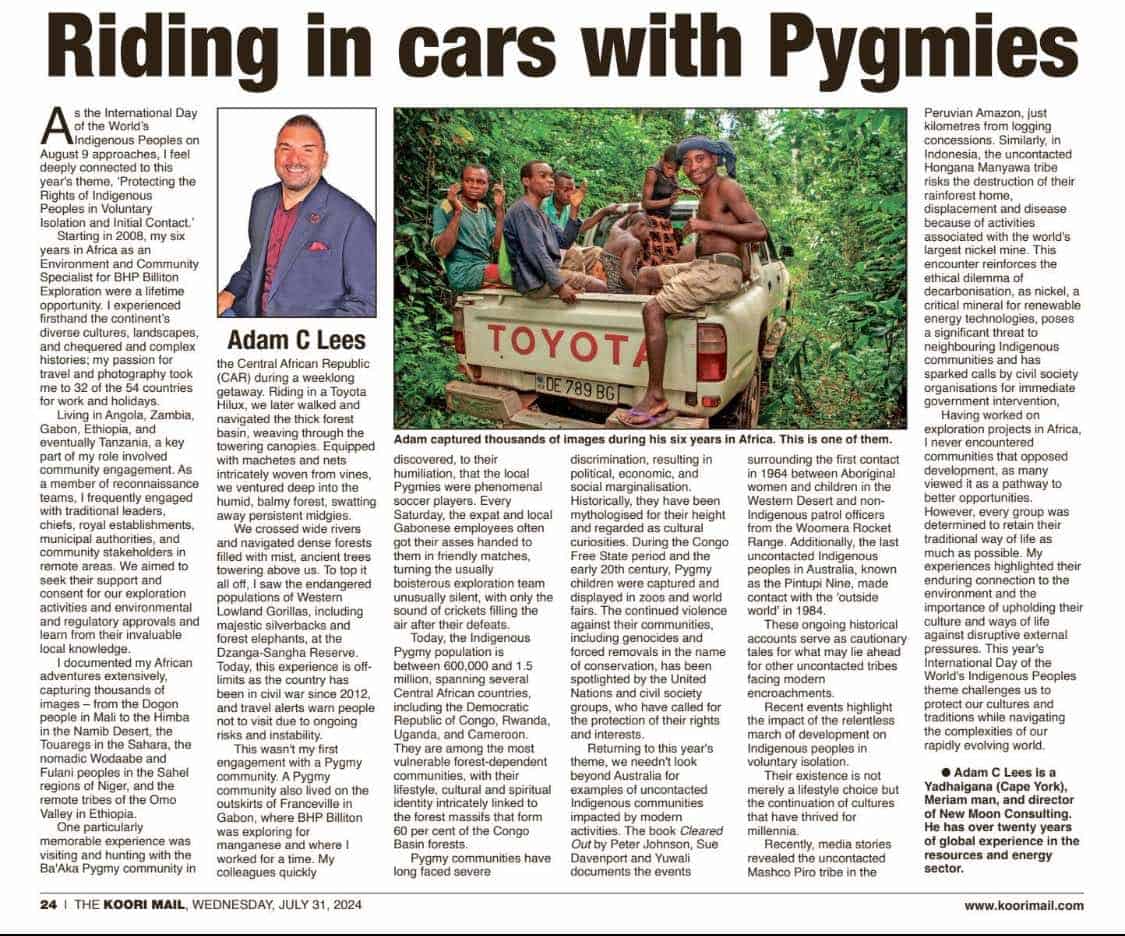

I documented my African adventures extensively, capturing thousands of images – from the Dogon people in Mali to the Himba in the Namib Desert, the Touaregs in the Sahara, the nomadic Wodaabe and Fulani peoples in the Sahel regions of Niger, and the remote tribes of the Omo Valley in Ethiopia.

One particularly memorable experience was visiting and hunting with the Ba’Aka Pygmy community in the Central African Republic (CAR) during a weeklong getaway. Riding in a Toyota Hilux, we later walked and navigated the thick forest basin, weaving through the towering canopies. Equipped with machetes and nets intricately woven from vines, we ventured deep into the humid, balmy forest, swatting away persistent midgies.

We crossed wide rivers and navigated dense forests filled with mist, ancient trees towering above us. To top it all off, I saw the endangered populations of Western Lowland Gorillas, including majestic silverbacks and forest elephants, at the Dzanga-Sangha Reserve. Today, this experience is off-limits as the country has been in civil war since 2012, and travel alerts warn people not to visit due to ongoing risks and instability.

This wasn’t my first engagement with a Pygmy community. A Pygmy community also lived on the outskirts of Franceville in Gabon, where BHP Billiton was exploring for manganese and where I worked for a time. My colleagues quickly discovered, to their humiliation, that the local Pygmies were phenomenal soccer players. Every Saturday, the expat and local Gabonese employees often got their asses handed to them in friendly matches, turning the usually boisterous exploration team unusually silent, with only the sound of crickets filling the air after their defeats.

Today, the Indigenous Pygmy population is between 600,000 and 1.5 million, spanning several Central African countries, including the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Uganda, and Cameroon. They are among the most vulnerable forest-dependent communities, with their lifestyle, cultural, and spiritual identity intricately linked to the forest massifs that form 60 per cent of the Congo Basin forests.

Pygmy communities have long faced severe discrimination, resulting in political, economic, and social marginalisation. Historically, they have been mythologised for their height and regarded as cultural curiosities. During the Congo Free State period and the early 20th century, Pygmy children were captured and displayed in zoos and world fairs. The continued violence against their communities, including genocides and forced removals in the name of conservation, has been spotlighted by the United Nations and civil society groups, who have called for the protection of their rights and interests.

Returning to this year’s theme, we needn’t look beyond Australia for examples of uncontacted Indigenous communities impacted by modern activities. The book ‘Cleared Out’ by Peter Johnson, Sue Davenport, and Yuwali documents the events surrounding the first contact in 1964 between Aboriginal women and children in the Western Desert and non-Indigenous patrol officers from the Woomera Rocket Range. Additionally, the last uncontacted Indigenous peoples in Australia, known as the Pintupi Nine, made contact with the ‘outside world’ in 1984.

These ongoing historical accounts serve as cautionary tales for what may lie ahead for other uncontacted tribes facing modern encroachments. Recent events highlight the impact of the relentless march of development on Indigenous Peoples in voluntary isolation. Their existence is not merely a lifestyle choice but the continuation of cultures that have thrived for millennia.

Recently, media stories revealed the uncontacted Mashco Piro tribe in the Peruvian Amazon, just kilometres from logging concessions. Similarly, in Indonesia, the uncontacted Hongana Manyawa tribe risks the destruction of their rainforest home, displacement, and disease because of activities associated with the world’s largest nickel mine. This encounter reinforces the ethical dilemma of decarbonisation, as nickel, a critical mineral for renewable energy technologies, poses a significant threat to neighbouring Indigenous communities and has sparked calls by civil society organisations for immediate government intervention,

Having worked on exploration projects in Africa, I never encountered communities that opposed development, as many viewed it as a pathway to better opportunities. However, every group was determined to retain their traditional way of life as much as possible. My experiences highlighted their enduring connection to the environment and the importance of upholding their culture and ways of life against disruptive external pressures. This year’s International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples theme challenges us to protect our cultures and traditions while navigating the complexities of our rapidly evolving world.

Adam C Lees is a Yadhaigana (Cape York), Meriam man, and Director of New Moon Consulting. He has over twenty years of global experience in the resources and energy sector.